Speculative - Komodo Dragons in Australia?

When people think about giant carnivorous reptiles, most people think of dinosaurs (often incorrectly as some paleontologists would tell you). But if you asked them about modern carnivorous reptiles that prey on man, the average person would say crocodiles, giant snakes, or the infamous Komodo Dragons

|

| (wikipedia.org) |

While they are currently found only on that small pocket of islands, they weren't alway restricted to just there. It was once believed that the Komodo dragon developed on those islands as a case of island gigantism (a biological phenomenon in which animals that would smaller on the mainland become giants on offshore islands). But it is now realized that the dragons are in fact relict population of giant carnivorous reptiles that lived not in the island of Komodo, but the continent of Australia.

While the Land Down Under is known for it marsupials and red sandy deserts, is also know for having a great number of reptiles. Amongst these reptiles are the varanitids, a group of mostly carnivorous reptiles that the komodo dragon and it's relatives (such as the Perentie, Australia's largest living lizard). Fossil records have shown that in Australia during the Ice Age, the komodo dragon actually roamed the Australian outback, along with the Perentie and the now-extinct Megalania (a giant relative, believed to be up to 20-30 feet in length).

If the Komodo Dragon roamed the Australian Outback back in the Ice Age, then it leads to this question:

How did it get to Komodo and it's surrounding islands?

Would you believe that the dragons got there via boats?

Despite how it sounds, that is precisely how scientists believe how the ancestors of the dragons got to the islands, by rafts of vegetation or even logs. Since sea levels were lower back in the Ice Age and reptiles wouldn't need food or water for an extended periods of times, it would be easy for the dragons (especially if they were young) to simply rode rafts and get to the islands of komodo within weeks to months.

But, this then leads to another question:

Why did the dragons survived on the Komodo islands, but died out in Australia?

|

| Megalania hunting (reptilis.net) |

That is a question that has been asked for not just the Komodo dragons of Australia, but the other megafauna of the Ice Age (Megalania, the Diprotodonts or rhino-sized wombats, Procoptodon or short-faced kangaroo, Thylacoleo or marsupial lion, etc.). Many scientists would agree that habitat change caused by climate change that happened at the end of the Ice Age, along with human activities (e.g. Fire Farming), was the main cause of the extinction of the herbivorous megafauna. And with the death of the prey, the predators that specialized in hunting other megafauna died out in toe, this would include the Australian Komodo dragons.

With the Komodo dragons of Australia gone extinct and with out scenario, it begs the question:

How could the Komodo dragon be back on Australia?

Well, with the lack of the large prey animals in Australia, it would be safe to say that the Australian dragons would not survive. But, the dragons did survive on the islands of Komodo and could it be possible for the dragons be able to drift back to Australia?

Well, it could be possible, but there is a couple catches:

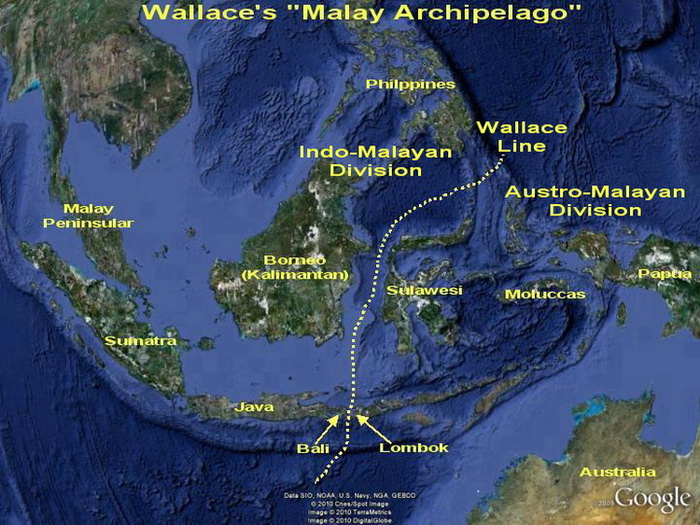

The ocean currents within the Wallace Line.

The Wallace Line, named after the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, is a faunal boundary line drawn by the said naturalist. An oceanic barrier that prevents the Asian and Australian fauna from intermixing, with the slight exception of the Wallacea region (islands where Asian and Australian flora and fauna do mix). And looking at the maps of the ocean currents, it would be extremely slim for the Komodo dragons to be able to drift back to Australia.

So, while it is extremely slim, it could be possible for the Komodo dragons to drift back to Australia (especially as infants since infant komodo dragons are arboreal) on rafts of vegetation. And with them being reptiles, not needing to eat or drink for extended periods of time, it could work.

And even if you get just females or just one female, it could still work since komodo dragons can do a process called parthenogenesis. This is basically being able to reproduce without the assistance of a male. However, due to the komodo dragon's chromosomes, they can only produce male offspring during this. If you have a group of females and just one of them does this, then it could be possible to start a breeding population from there.

But if you get just one female and she does this? Well, inbreeding would unfortunately happen and the issues of inbreeding (e.g., inbreeding depression) could happen. But, there is the possibility of a phenomenon occurring that is called "purging selection". This is an extremely rare phenomenon in when the reduction of the frequency of a deleterious allele (traits that come about during inbreeding), caused by an increased efficiency of natural selection prompted by inbreeding. like mentioned before, it is a rare occurrence, but it's believed to have happened with invasive species (e.g., ladybird beetles).

So, if such a occurrence happens with the colonizing dragons, then it could work. If they did, it could be more likely at the northwestern or, more likely, western coast (a map shows a possible current route) and could spread out from there by following the coastline northeastward.

|

| (https://indopacificimages.com) |

Lack of large prey animals!

While the young can be able to survive on small animals, the adults might have a hard time feasting since that the large megafauna (rhino-sized wombats and such) that their ancestors feasted on are gone. So, game over?

Well, maybe not.

There a possibility of why the ancestral dragons went extinct is not just the loss of the large megafauna due to climate change, but the macropods (kangaroos and kin) and emus were still at relatively small population at the time. And after their extinction, the macropod and emu populations exploded (also thanks to humans since their fire farming practices help create the habitats that these species thrive in). With this, it could be possible that the large dragons could feast upon the macropods and emus, along with other possible sources of food.

So, with how they could come back and how they could sustain themselves explained, now we can get into on what the effects the Komodo (or maybe more properly called 'Australian') dragons would have on the Land Down Under.

Australian Dragon Ecology

Just like on the islands of Komodo, the dragons' diet would be widespread, feasting upon any kind of vertebrate that they can overpower. When they are infants, they are arboreal and would feast upon birds, small lizards, invertebrates, and small tree-dwelling mammals (sugar gliders, small possums, etc.). But this would make compete with the tree-dwelling monitor lizards, such as the lace monitor (which is more closely related to the dragon than the other monitor lizards).

|

| (hasitakomodo.com) |

|

| (Ecological Society of Australia) |

As with any creature of the Outback, the dragons would be affected by the constant wildfires. When these fires appear, they would either escape the fires, perish in the flames, or (if the fires were slow enough) hunt for any animal that tries to escape the fire. And after the fire has passed, the dragons would feast upon the charred bodies of any creature unfortunate enough to be caught by the fire (their own barbecue, if you will).

What would the dragons' relationship with the predators that now roam the continent (crocodiles, perenties, and, fellow recent arrivals, dingos)? I would say that they would be competitors, prey, and predators of the dragons. Competitors, because they would be competing for the same prey items Prey, because the dragons are not picky about what animal they eat and would gladly hunt and feast on them if they could overpower them. Predators, because on given circumstances, these animals could hunt and consume the dragons (crocodiles when they reach a certain size, dingos when in packs, and perenties when the dragons are infants). Other predators, when the dragon are infants, would be pythons, other monitor lizards, and birds of prey.

An interesting note would be that while thylacoleo and megalania are extinct, the tasmanian devils and tigers did roam Australia for a while after the ice age. With the thylacines and devils, they would definitely be the competitors, prey, and predators of the dragons. The devils would consume young dragons, compete with the dragons with carcasses, and would be eaten by full-grown dragons. The tasmanian tigers (or thylacines) would probably be less involved with the dragons. They would be hunted by the dragons (both young and old), hunting their young would be a minimum, and thylacines would wolf down their meals before the dragons came in to steal their kills.

Another competitor, prey, and predator that the dragons would deal with are humans.

Past and Modern Cultural effects of the Dragons

The first human culture to be in contact with the Australian Dragons would be the Australian Aborigines, who scientists believe arrived on the island continent about 65,000 years ago. As hunters and gatherers, the aborigines would be competing with, hunted by, and hunting the Australian dragons. They would be competing with the dragons because they would hunt for the same prey animals, they would be hunted by dragons by a certain size, and they would hunt dragons of any size (since they hunt and consume their younger relatives as well), though it would be difficult because the dragons have bone underneath their skin which act like chain mail.

|

| Aboriginal rendering of Dirawong (Cryptid Wiki) |

In their culture, just like their smaller cousins, the dragons would have a prominent figure in the aborigine's culture and mythologies. Artwork of them would be shown as both a food source and a spiritual motif, especially as a spiritual motif due to their large size and could be able to both provide them food and to make them into food as well. With many tribes throughout the whole continent, from the Ayabakan to the Wadajarri, would definitely have their own word for these dragons. One such name that is possible is the Dirawong, which is a name for a spiritual being that takes the form of a goanna and is one of the Creator beings of the Bundjalung. And it would also be seen as of creature of the Dreamtime, which is a time when the Ancestral Spirits ruled the land and created all creatures and important geographic areas.

But, by 17th century, things are gonna change as European explorers have 'discovered' Australia. Whether they would see the dragons during these first visits would be unknown since that just any large predator, their populations are smaller than that of their prey. But they might be larger than that of the mammals since they don't need to eat as often as mammalian predators need to. But even so, it would be possible that they might see dragons more often than dingos.

Undoubtedly, when Europeans first see these reptiles, would be utterly terrified of these reptiles and see them as monsters or dragons of mythology (so it would be fair to think that they would call them 'dragons' as we don in the real world). Interestingly, in this scenario, the dragons would be known for far longer and more so than they would be in our reality. This is because in our reality, the Komodo dragon would not be known to the western world until 1910, centuries after Australia was discovered!

As Europeans move into Australia, the dragons would definitely be in the back of their minds. During the penal colonial days, the presence of the dragons, they would be considered as a deterrent for escaping. Much like the dingos, crocodiles, and tasmanian tigers throughout European conquered Australia, the dragons would be hunted for protection of human life and livestock or even out of fear. Also, the hunting of their prey and destruction of their habitats would definitely endanger the dragons.

But, while the Europeans would definitely mean trouble for the dragons, what they would bring might be a blessing for them as well. And what I mean by that is the species that they bring to Australia with them. Some of them would be blessings, others would be mixed, and some would be all bad for them. Below will be a list of the introduced species that would have an affect on the dragons:

Brumbies (feral horses) and Donkeys

Pros: Provide the dragons a large amount of meat.

Cons: Their erosion causing hooves can be destructive to their habitat

Dromedary Camels

Pros: Provide the dragons a large amount of meat.

Cons: Constantly moving and probably live in areas where dragons couldn't live in.

Water Buffalo and Banteng

Pros: Provide the dragons a large amount of meat.

Cons: Cloven hooves and wallowing would destroy their habitats

Pigs

Pros: Provide food for the dragons.

Cons: Uprooting and cloven hooves would destroy habitats and they would dig up and eat dragon eggs.

|

| Like on Komodo, Australian Dragons would feast on feral goats (image from Daily Express) |

Goats

Pros: Provide food for the dragons.

Cons: Browsing and cloven hooves would disrupt their habitat.

Rabbits and Hares

Pros: Provide dragons a source of meat.

Cons: Intense grazing would cause immense soil erosion and disrupt the grasslands

Feral cats and Red Foxes

Pros: Provide the dragons a source of food.

Cons: Would compete with younger dragons with prey and would be hunted by them.

Deer (Red, Sambar, Rusa, Fallow, Chital, Hog)

Pros: Provide the dragons a source of food.

Cons: Cloven hooves and browsing would disrupt their habitat.

Cane Toads

Pros: Lower the populations of competing monitor lizards.

Cons: Consumption of these toads would kill the dragons.

The distribution of these introduced species can affect the future distribution of the dragons, some would be expanding them (e.g., the hoofed animals) or limiting them (e.g., Cane Toads). And this would even make them valuable to rangers for managing invasive species. But, while they could help, they would not be a good analog for mammalian predators since they do not eat as often as a mammal of the same weight would need.

In more recent times, the presence of the dragons would have affected the the course of scientific world and the outlook of Australia. In the scientific world, the Australian dragons would be of great scientific interest, they would even be used as models for studying the predatory ecology of large prehistoric reptiles (from Dimetrodon to Dinosaurs, in a time when they were thought to be cold-blooded). Scientifically, they would probably be called Varanus australis or Varanus major (for it's large size). Commonly, they would be called the "Australian Dragon", "Outback Dragon" or, incorrectly, the "Last Dinosaur". But, would also be known as the Bane of Cattle Rustlers and Sheep Herders.

|

| Like in Komodo, Australian Dragons would be popular for tourists (This photo of Top Komodo Tours is courtesy of Tripadvisor) |

As one would expect, the dragons would be in endangered due to hunting, habitat destruction, and invasive species (mostly cane toads). With large tracts of land being either cattle stations (large Australian ranches) or uninhabited, this would give the dragons a bit of hope. And with population booms of some native prey animals and introduced species (due to dingo numbers dropping via hunting), these areas would be their havens. And if the dragons' population needs a genetic boost? Well, the islands of Komodo (still be discovered recently) could have a population of dragons that could provide more genetic diversity for the Australian dragons.

REFERENCES

Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; et al. (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago" (PDF). Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310.

http://ielc.libguides.com/sdzg/factsheets/komododragon/diet

https://indopacificimages.com/indonesia/indonesian-throughflow/

https://www.aboriginal-art-australia.com/aboriginal-art-library/understanding-aboriginal-dreaming-and-the-dreamtime/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982211001242

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351989419301180

Jessop, T. S., Ariefiandy, A., Forsyth, D. M., Purwandana, D., White, C. R., Benu, Y. J., ... & Letnic, M. (2020). Komodo dragons are not ecological analogs of apex mammalian predators. Ecology, e02970.

Purwandana, D., Ariefiandy, A., Imansyah, M. J., Seno, A., Ciofi, C., Letnic, M., & Jessop, T. S. (2016). Ecological allometries and niche use dynamics across Komodo dragon ontogeny. The Science of Nature, 103(3-4), 27.

THE BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY OF THE KOMODO MONITOR. Walter Auffenberg. University of Florida-University Presses of Florida, 1981.

Comments

Post a Comment